Every year, every day and every second, we process millions and billions of information units. Everything that surrounds us is information. From the bird singing or the text message you received this morning, to that sticky news feed calling for you with all sorts of tricks and notifications — this is the information that our brain is about to process.

We’ve been taught that time is the most valuable and finite asset in our lives. How we spend it and with whom we spend it not just matters, it defines who we are. But what’s even more important than time is our attention.

In the world today, it feels like we live at the forefront where everyone and everything is trying to get a little piece of that from us. Living a life in that endless stream sometimes makes it hard to listen to your own self and your ideas — things that make us different.

Invisible tail

Attention is more than time. There is a study[1] by Shamsi Iqbal and Eric Horvitz on attention residue that shows even brief interruptions, such as checking an email notification, can take about 10 minutes of our focus and add an additional 100% to 200% of that time for post-activity information processing.

Every time we engage with any information, it leaves a long, invisible tail of brain work, even if we don’t recognize it. And the more impulsive the information, the longer that tail is.

Healthy food builds healthy bodies, and healthy information builds healthy minds. Just like fasting makes our bodies produce better results, information fasting makes our brains produce better work.

Silence is also music

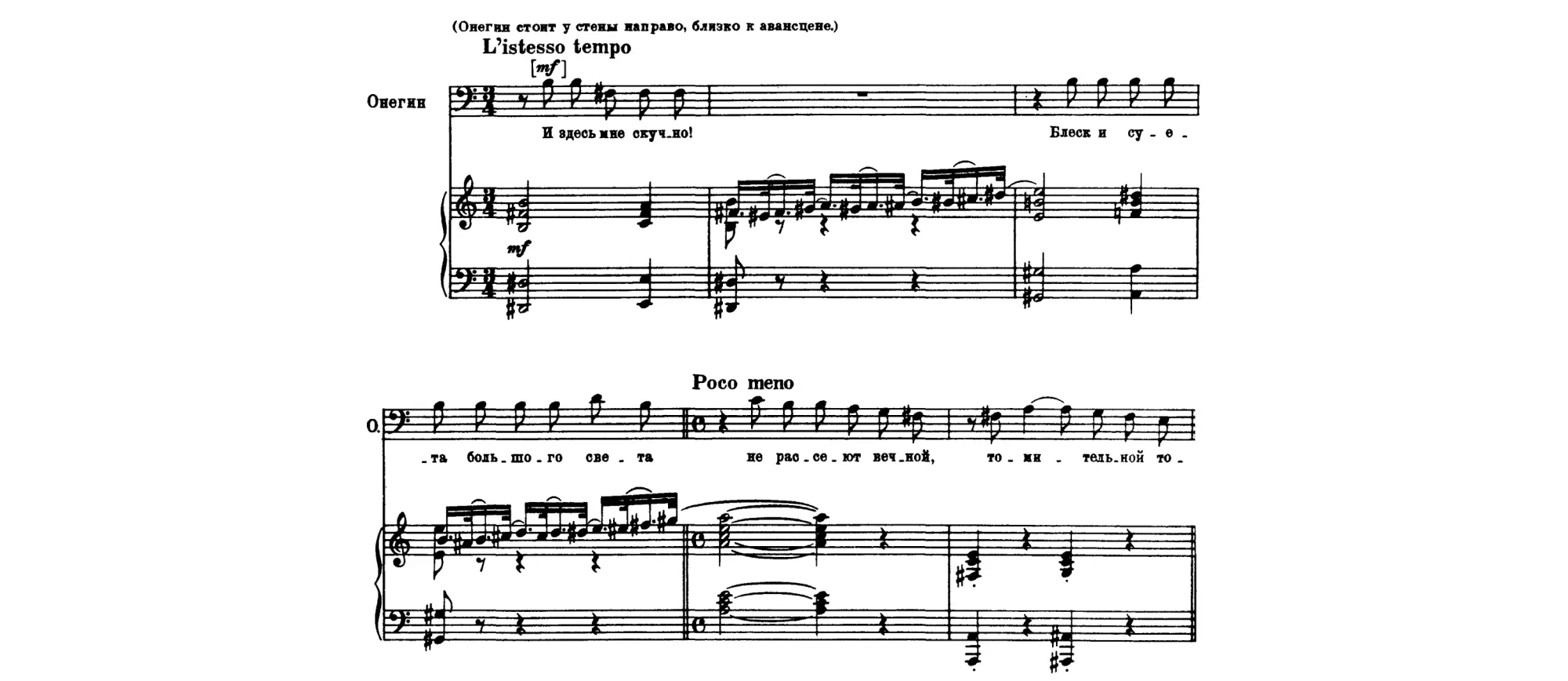

You would probably never thought about it, but silence in music is one of the most powerful tools. In 2014, I was preparing for my debut as Eugene in Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin. I was still in my third year at the conservatory at the time, and my professor was eager for me to debut early. It’s usually uncommon to debut in the main role of an opera at that age, but things were moving faster for me, and I knew I was ready for that.

There is a famous scene and monologue, “I zdes' mne skuchno” (“И здесь мне скучно”), that Onegin sings at the beginning of the final act, right after the brilliant opening Polonaise. I remember rehearsing the monologue with the orchestra and feeling unsatisfied with how it was all coming together.

One day, the conductor stopped me and asked why I was rushing through that place. I said I thought I had to keep the tempo right so the action would keep tense. His face filled with a little laugh and he said to me, ‘Of course you’re right. But if you want to have a deeper thought for your monologue, you have to learn to listen to the pauses. Silence is also music.’

A secret passage to creativity

Silence doesn't mean emptiness — just like pauses are also music. Sometimes, silence even more important than the notes we hear. It concentrates attention for both, the performer and the audience. You can’t be truly prepared for the next phrase if you don’t get the pause right. Silence is like a secret passage to your creativity, authenticity, and focus.

The advice I got from conductor was really helpful as I worked on my role. The monologue got enough air and the shape I was looking for as the pauses were played. We ended up closing the final act to a standing ovation and celebrated with the stage crew in the best traditions of classical theatre.

As the time passed by I realised that advice wasn't just about how to make better music, it was about how to get better at everything. We often underestimate how important silence is, but the most original and authentic work ever created was born in silence. Whether it’s music, painting, wireframing, or coding, silence brings far more than we expect.

Find your quiet place. Create more work. And let the music play.

k.

References

- Iqbal, S. T., & Horvitz, E. (2007). Disruption and Recovery of Computing Tasks: Field Study, Analysis, and Directions. Retrieved from source